Dessert isn’t usually the problem.

The crash that follows is.

Most people don’t regret dessert while they’re eating it. They regret it 45 minutes later when energy dips, sleepiness creeps in, focus drops, or cravings suddenly return. That uncomfortable swing from high to low is what makes dessert feel like a mistake.

But often, the issue isn’t the sweetness itself.

It’s the structure.

Most desserts are designed for speed. Refined flour, sugar, syrups ingredients that digest quickly and enter the bloodstream fast. When sugar arrives all at once, blood glucose rises sharply. Insulin follows quickly to bring it down. And when that drop happens rapidly, you feel it.

Fatigue. Brain fog. Hunger. More sugar cravings.

The body isn’t “punishing” you. It’s simply responding to a fast spike.

Dessert architecture is about changing that response without eliminating dessert.

The Real Question: What Is Your Dessert Built With?

Think of two scenarios.

In the first, you eat a piece of cake on an empty stomach at 4 pm. It’s mostly refined flour and sugar. Within minutes, blood sugar climbs. An hour later, you’re sleepy and reaching for something salty or sweet again.

In the second, you have that same cake after dinner ... a meal that included protein, vegetables, and some fat. The cake digests more slowly because it’s entering a system already processing other nutrients. The rise is gentler. The fall is softer.

Same cake. Different outcome.

That’s architecture.

Slowing the Spike: What Actually Helps

When sugar is eaten alone, it moves quickly. When paired thoughtfully, it behaves differently.

Three things make the biggest difference:

1. Protein Acts as a Stabiliser

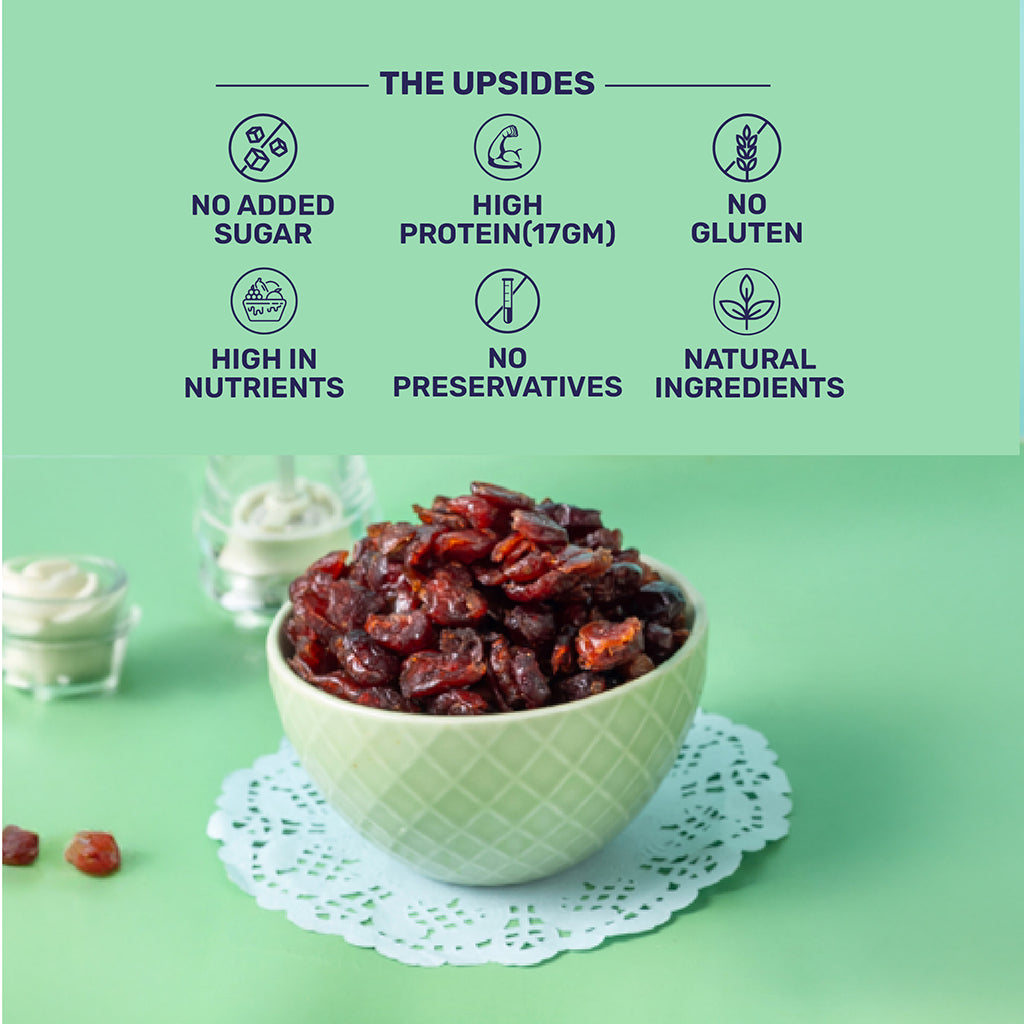

Protein slows gastric emptying and reduces the sharpness of a glucose spike. This is why desserts that include yogurt, milk, paneer, or nuts often feel more satisfying and less destabilizing than sweets made purely of sugar and flour.

Even something as simple as having dessert after a protein-rich meal can change the impact.

2. Fat Adds Friction

Fat slows digestion. It increases satiety. It prevents sugar from racing through your system.

This doesn’t mean adding excessive butter to everything. It means understanding why ice cream with nuts behaves differently than sorbet alone, or why dark chocolate feels steadier than sugary candy.

3. Fibre Cushions the Rise

Fibre physically slows absorption. Fruit, seeds, whole ingredients — these help sugar enter the bloodstream at a more measured pace.

It’s not about turning dessert into a “health food.” It’s about giving it some structure.

Context Matters More Than You Think

Dessert on an empty stomach behaves very differently from dessert after a balanced meal.

When you’ve already eaten protein, fibre, and fat, digestion is slower. Blood sugar rises more gradually. Insulin responds in a more controlled way.

This is why “dessert after dinner” often feels different from “dessert as a snack.”

Timing isn’t about rules. It’s about physiology.

What Dessert Architecture Looks Like in Real Life

This isn’t about replacing your favourite sweets with protein bars.

It’s about small design shifts:

-

Having mithai after dinner instead of mid-afternoon

-

Pairing chocolate with almonds instead of eating it alone

-

Choosing fruit with yogurt rather than fruit juice

-

Eating ice cream with a meal instead of on an empty stomach

-

Keeping portions moderate so the total glucose load isn’t overwhelming

The dessert doesn’t disappear. It just becomes metabolically smarter.

Why This Matters Beyond One Afternoon

Repeated large spikes followed by crashes can influence:

-

Energy stability

-

Hunger signals

-

Cravings patterns

-

Insulin sensitivity over time

When desserts are structured better, energy feels more predictable. Cravings don’t snowball into all-evening grazing. Guilt reduces because the aftermath isn’t dramatic.

And ironically, when you stop experiencing extreme crashes, you often need less sugar overall.

This Isn’t About Control

Dessert architecture isn’t about micromanaging every bite. It’s about understanding how your body works and making small adjustments that support it.

You don’t need to eliminate sweets.

You don’t need “sugar-free” everything.

You don’t need perfection.

You need better structure.

The next time you reach for something sweet, don’t ask, “Should I have this?”

Ask, “How can I build this so it works better for me?”

Dessert doesn’t need to be cancelled.

It just needs better architecture.

Comments (0)

Back to Learn